Issue 2: Theory and Practice

The Neighborhood is the New Factory | Liz Mason-Deese

The movements of the unemployed, which first emerged in Argentina in the mid-1990s, challenge traditional representations of the unemployed as lacking political agency and revolutionary potential. While many Marxists and labor organizers have maintained the latter position, Argentina’s recent history paints a different picture: the militant organization of the unemployed across the country was instrumental in overthrowing the neoliberal government in 2001 and steering the course the country would take following the economic crisis. Movements of the unemployed in Argentina are redefining work through their organizational practice, discourses around labor, and active creation of different forms of production and reproduction.

Against Humanities: The Self-Consciousness of the Corporate University | Mark Paschal

A standard feature of the hand-wringing associated with the crisis of the university is a fixation on the humanities. After all, for those of us in the so-called creative and critical fields, illustrating, visualizing and – dare we say it – branding the crisis is a new and unique opportunity to show off. This is what we went to school for, isn’t it? Take a recent event at Cornell University, which dramatized the question with the following thought experiment: after some sort of maritime disaster (details are scarce), a group of undergraduates commandeers a life raft. As luck would have it, they have a bit of space left – but, tragic twist of fate, the only people left to save are professors. Instead of giving up the seats to their elders, our clever young narcissists make the professors present a case as to why they deserve the remaining spot on the life raft.

When Professors Strip for the Camera | James Cersonsky

If TED took a turn to leftist (or any) critique, Žižek, the professor of “toilets and ideology,” would be the keynote speaker. The irony of the animated lecture, “First as Tragedy, Then as Farce,” is that a diatribe on “global capitalism with a human face” would get over 900,000 views on YouTube. With YouTube’s help, the academy where Žižek’s persona was born is an increasingly visible terrain of so-called “cultural capitalism.” The last decade has witnessed a revolution in open courseware, a source of short-circuit consumption in which anyone with a computer can drink elite university Kool-Aid without earning credit. The movement has been so explosive – the Hewlett Foundation, which provides the mother lode of funding for university initiatives, supported a whole book on it, Taylor Walsh’s 2011 Unlocking the Gates – that one wonders how long the political economy of education that it anchors, contra Žižek’s hipster-friendly fantasies of consumerist dystopia, will last.

History and Politics: An Interview | Gopal Balakrishnan

Just as we clearly see that Marx’s economic thinking arises out of a critique of classical political economy, and that in turn was made possible by a prior critique of idealist philosophy, we also have to see the problems of revolutionary politics that Marx is addressing as a critical engagement with the past history of political thought. There are specific category problems, as well as intertwined historical subject matter in an engagement with that side of Marx, and Marx’s own engagement with this lineage of thinkers – Hegel as a legal and political thinker, clearly, but Hegel’s thought as a culmination of a tradition of legal and political thinking going back to Aristotle. That’s something which has been underscored by others in the Marxist tradition, you could think of Althusser and Colletti, who also had works which were explicitly about the political writers before Marx, who in some way introduce or delineate the problems of politics and history that Marx will subsequently take up in his accounts of the class struggles and civil wars of the times that he was living in.

To the Party Members | Larisa K. Mann

The sound and image of a drum circle may be one of the most easily-mocked moments associated with the Occupy movements. But the role of music in the movement, and its relation to protests and political action in general, bears closer investigation, beyond the drum circle. The concept of “protest music” can obscure some of music’s most powerful aspects as a social force. For many involved in Occupy, the specific relationship between the music being played and the people who hear it has not been thought through very carefully – and this weakness can reinforce political weaknesses. Indeed, when even Salon.com can call 100 tracks of Occupy-themed music “shapeless and safe,” we might ask ourselves what this protest music is missing.

Be the Street: On Radical Ethnography and Cultural Studies | Gavin Mueller

There wasn’t much to wax romantic about in the Detroit music scene at that time. The culture industries were undergoing a restructuring for the immaterial age. Vinyl was no longer moving. Local radio and local music venues had gone corporate, squeezing out local music. DJs who wanted local gigs had to play Top 40 playlists in the suburban megaclubs instead of the native styles of electronic music that had given Detroit mythic status around the world. Many had given up on record labels entirely. Everyone looked to the internet as the saving grace for record sales, promotion, networking – for everything, practically. Some of the more successful artists were attempting to license their tracks for video games. Almost everyone had other jobs, often off the books. I wasn’t embedded within this community, as an anthropologist would be. Instead, I made the 90 minute drive to Detroit when I could, and spent the time interviewing artists in their homes or over the phone.

In Defense of Vernacular Ways | Sajay Samuel

The crises continue to accumulate: the economic crisis, the ecological crisis, the social crisis, crises upon crises. But as we try to create “solutions,” we distressingly find ourselves up against a limit, discovering that the only alternatives we can imagine are merely modifications of the same. We have forgotten how to think the new – or the old. Ivan Illich, priest, philosopher, and social critic, is not a figure that most would expect to read about in a Marxist magazine. But he identified this problem long ago, and argued that the only “way out” was a complete change in thinking. His suggestion, both as concept and historical fact, was the “vernacular.”

The Terrain of Reproduction: Alisa Del Re’s “The Sexualization of Social Relations” | Anna Culbertson

In an era when the exploits of Silvio Berlusconi’s “private” life seem to have categorically obliterated any progress towards sexual equality achieved during the Italian feminist movement of the 70s, it is essential to remember what was once accomplished. Although second-wave feminism was already a well-established network of debates in the U.S. by 1970, Italian women influenced by workerist writings of the feminist ilk, most notably Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Selma James’s The Power of Women and the Subversion of the Community, set out to initiate battles over issues such as abortion and divorce. Feminist currents both from within and independent of workerist movements then spread with a fierce momentum that would endure through the decade.

The Sexualization of Social Relations | Alisa Del Re

Women, researchers, feminists, in an institutionalized group with a research topic both precise and isolated from the traditional scientific context, with the palpable need to find new methodologies, new avenues, of reconstructing the subjects in their entire form, the same subjects that in traditional science become chopped, mutilated, seen in quantity and without quality. And this in “science,” to impose a new “scientific” point of view that concerns women and their work, the sexuality of social relations as an “existent.” As a method, bringing scientists together from different disciplines and different “schools” (although here we limit ourselves to the social sciences) is nothing new: interdisciplinary research in the humanities has been fruitful in various fields. But the novelty lies in the fact that it is the woman-subject that is studying the woman-object.

Towards a Socialist Art of Government: Michel Foucault’s “The Mesh of Power” | Christopher Chitty

How surprising the events of May 1968 must have seemed to Michel Foucault is suggested by a remark made to his life-long partner Daniel Defert in January of that year, following his nomination for a faculty position at the University of Paris Nanterre. “Strange how these students speak of their relations with profs in terms of class war.” Interpretations of this remark will reveal a lot about one’s received image of the late philosopher. Among figures of the New Left he had earned a reputation as an anti-Marxist for disparaging public comments about Jean-Paul Sartre, and the apparent heresies of Les mots et les choses. A younger generation of left-leaning intellectuals, activists, and agitators, exposed only to later portraits of the radical philosopher – the author of Discipline and Punish, megaphone in hand, rubbing shoulders with Sartre and other ultra-gauchistes at protests in the streets of Paris – will probably find the confession disconcerting. Is it possible that he was taken off guard by the political sparks that would set alight le mouvement du 22 mars? He did, after all, arrive in Paris post festum, participating in some of the final rallies at the Sorbonne in late June.

The Mesh of Power | Michel Foucault

How may we attempt to analyze power in its positive mechanisms? It appears to me that we may find, in a certain number of texts, the fundamental elements for an analysis of this type. We may perhaps find them in Bentham, an English philosopher from the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th century, who was basically the great theoretician of bourgeois power, and we may of course also find these elements in Marx, essentially in the second volume of Capital. It’s here, I think, that we may find some elements that I will use for the analysis of power in its positive mechanisms.

Underground Currents: Louis Althusser’s “On Marxist Thought” | Asad Haider and Salar Mohandesi

When Perry Anderson wrote in 1976 that “Western Marxism” could be considered a “product of defeat,” he was referring to the catastrophes and betrayals that framed the period from 1924 to 1968. In retrospect, this seems like foreshadowing. The intervening decades have seen not simply a defeat for the workers’ movement but its total dissolution – the collapse of the institutions that once made it an undeniable social force, and the rollback of the reforms it had won from the state. In our situation it has become difficult to say what “Marxism” really is, what distinguishes it as a theory, and why it matters. But this is by no means a new question. And of all the definitions and redefinitions of Marxism, Louis Althusser’s were perhaps the most controversial. In 1982, just before François Mitterrand’s turn to austerity, Althusser began to draft a “theoretical balance sheet.” He wrote “Definitive” on the manuscript, and never published it.

On Marxist Thought | Louis Althusser

If this recourse to the side of the thought of Marx and Engels is still available to us, unfortunately the same does not go for the communist parties. Built on the base of the philosophy of the Manifesto and Anti-Dühring, these organizations hold only on bases that are all through and through frauds, and on the power apparatus that builds itself in the struggle and its organization. The parties, resting on the unions of the labor aristocracy, are the living dead, who will subsist as long as their material base lasts (the unions holding power in the works councils, the parties holding power in the municipalities), and as long as they are capable of exploiting the dedication of the class of proletarians and abusing the condition of the sub-proletarians of subcontracting. From now on there is an irreconcilable contradiction between the strokes of genius in the thought of Marx and Engels and the organic conservatism due to the parties and the unions.

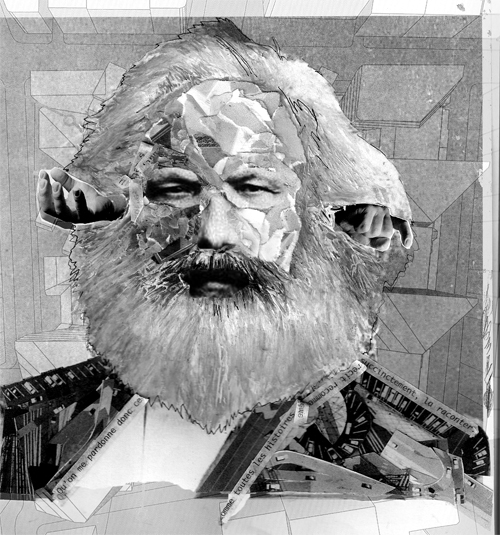

Illustration by Millen Belay.

Viewpoint Magazine

Viewpoint Magazine